The Cloughton Stone Circle

“The traveller who would see the stone circle on Cloughton Moor must take the road to the Falcon Inn”, according to AN Cooper, the secretary of the East Riding Antiquarian Society, “not that the inn has anything to do with the object he is in search of, but it may not be out of place to advise that a good meal of eggs and turf cakes may not be a bad preliminary to the business at hand." The Scarborough Mercury, 1920.

Compared to the grand old clocks of Stonehenge and Avebury, the little stone circle on Cloughton Moor is a pocket watch tucked away in the waist coat of North York Moors. But like any small timepiece, size adds to its charm, and though many of the cogs are missing we can still easily imagine the jeweller’s hand in its construction, setting it off on its journey, on its fixed point through SpaceTime.

The key to stone circles is the surrounding landscape. Many circles are surrounded by a ridge line or escapement which funnels or t the sunlight at dawn and sunset on certain days. Notches on the escapement made for the moon and stars can also be marked out.

British archaeologist Aubrey Burl hypothesised that you could calculate the size of an ancient population from the size of their stone circle using the formula πR2 given that standing in a crowd packed shoulder to shoulder or standing in a crowd comfortably with a little personal space would take up 0.6m to 2.6m depending on how popular the performance was. To the antiquarians, a large stone circle suggested an area of dread due to 'high witch content'. A small stone circle suggested the areas witch activity was problematic but more of an occasional nuisance and anti-social. With his tongue in his cheek, Burl advised, “always work clockwise when measuring stone circles for fear of rousing the devil”.

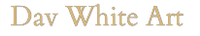

The Cloughton circle was given the title the Druids Circle on the map drawn up by the antiquarian Robert Knox in 1820. He thought the circle originally had 24 stones. After much destruction, only 15 fifteen remain. Today, a few stones are hanging or have fallen or been broken. The stones are no higher than four feet and the circle has a circumference of 32 feet.

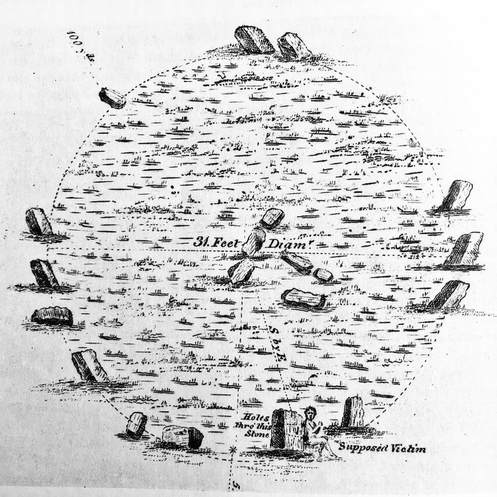

A large flat stone about four feet by two once lay at the centre and may have formed part of a burial chest. Many beautiful cup and ring markings covered it and it was thought to be one of the best examples of rock art in the area. It is now in the care of Scarborough Museum along with a few other stones that were rescued from the site by a Mr Tissiman, secretary of Scarborough Philosophical and Archaeological Society, as the stones were being removed from site and used for road mending in the 19th century.

Knox seemed both fascinated and outraged by the ancient Britons and their “wretched and crude” existence. His writing, though an invaluable source of knowledge, is written in a style that is often difficult to fathom, being both speculative and expressive of his moral outrage. Of the Cloughton stone circle, he writes: “These stone-pillars are as rough as the patriarchal altars of the Israelites. The human offerings to Apollo or to the Sun sat on a stone sacrificial seat with their backs to a perforated pillar, bound to it by thongs, with their faces south east to behold the deity (at dawn) while being immolated”.

His drawing shows a stone with a hole and depicts the bound victim ready for sacrifice. This brutality represented the prevailing opinion in the 19th century of the ancient Britons. After a recumbent stone at Stonehenge was labelled ‘the slaughter stone’, every stone circle in the country took on an air of sinister horror.

Later, in the more rational 20th century, archaeologist Frank Elgee suggested the Cloughton circle was in fact a burial circle. He suggested that many tumuli have a ring of stones around the base. A burial circle may have been a simple burial mound with a ring of stones but without the usual earthen mound. So the druid circle at Cloughton may have simply been a lazy tumulus, far removed from the description of Knox’s pagan horde baying for gore on Cloughton Moor.

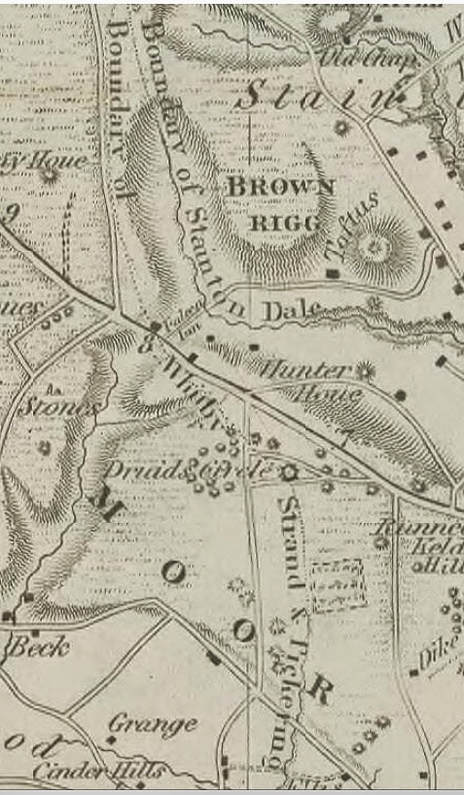

Knox explained that the original name for the stone circle at Cloughton was simply 'standing-stones'. He suggested that a perforated stone within the circle was a sacrificial pillar; “dedicated to Terminus, the ancient god of boundaries, who has in some manner protected this old place”. He explains that the location of the circle is named in the Whitby Abbey register as 'Swinestischarge'; a pigsty, “possibly used by the early monks of the abbey out of the hatred of the thing... too wreak their vengeance on this very ancient heathen fane by keeping their swine in this place". There are a number of stone circles in Britain that are of the same name, a name perhaps invoking Christ's Sermon on the Mount; "neither cast ye pearls before swine", do not give what is holy to those who will never accept you. However, this place was then adopted as one of the areas most important boundary marker, " … Cursed is he that removeth the landmarks! Cries Knox.- (Deut. XVii 17!!). The ancient boundary of The Liberty of Whitby Strand& Pickering Lythe passes through the circle and a line of a processional avenue of stones described by Knox may have been the line of Whitby Strand boundary stones that are still visible by the side of the fields today.

The Whitby Abbey register states that a cross-shape was added to one of the stones in the 17th century to mark it as part of the parish boundary, perhaps illustrating that the circle has always been a meeting place. This cross stone is still in situ.

Dav White Art

Compared to the grand old clocks of Stonehenge and Avebury, the little stone circle on Cloughton Moor is a pocket watch tucked away in the waist coat of North York Moors. But like any small timepiece, size adds to its charm, and though many of the cogs are missing we can still easily imagine the jeweller’s hand in its construction, setting it off on its journey, on its fixed point through SpaceTime.

The key to stone circles is the surrounding landscape. Many circles are surrounded by a ridge line or escapement which funnels or t the sunlight at dawn and sunset on certain days. Notches on the escapement made for the moon and stars can also be marked out.

British archaeologist Aubrey Burl hypothesised that you could calculate the size of an ancient population from the size of their stone circle using the formula πR2 given that standing in a crowd packed shoulder to shoulder or standing in a crowd comfortably with a little personal space would take up 0.6m to 2.6m depending on how popular the performance was. To the antiquarians, a large stone circle suggested an area of dread due to 'high witch content'. A small stone circle suggested the areas witch activity was problematic but more of an occasional nuisance and anti-social. With his tongue in his cheek, Burl advised, “always work clockwise when measuring stone circles for fear of rousing the devil”.

The Cloughton circle was given the title the Druids Circle on the map drawn up by the antiquarian Robert Knox in 1820. He thought the circle originally had 24 stones. After much destruction, only 15 fifteen remain. Today, a few stones are hanging or have fallen or been broken. The stones are no higher than four feet and the circle has a circumference of 32 feet.

A large flat stone about four feet by two once lay at the centre and may have formed part of a burial chest. Many beautiful cup and ring markings covered it and it was thought to be one of the best examples of rock art in the area. It is now in the care of Scarborough Museum along with a few other stones that were rescued from the site by a Mr Tissiman, secretary of Scarborough Philosophical and Archaeological Society, as the stones were being removed from site and used for road mending in the 19th century.

Knox seemed both fascinated and outraged by the ancient Britons and their “wretched and crude” existence. His writing, though an invaluable source of knowledge, is written in a style that is often difficult to fathom, being both speculative and expressive of his moral outrage. Of the Cloughton stone circle, he writes: “These stone-pillars are as rough as the patriarchal altars of the Israelites. The human offerings to Apollo or to the Sun sat on a stone sacrificial seat with their backs to a perforated pillar, bound to it by thongs, with their faces south east to behold the deity (at dawn) while being immolated”.

His drawing shows a stone with a hole and depicts the bound victim ready for sacrifice. This brutality represented the prevailing opinion in the 19th century of the ancient Britons. After a recumbent stone at Stonehenge was labelled ‘the slaughter stone’, every stone circle in the country took on an air of sinister horror.

Later, in the more rational 20th century, archaeologist Frank Elgee suggested the Cloughton circle was in fact a burial circle. He suggested that many tumuli have a ring of stones around the base. A burial circle may have been a simple burial mound with a ring of stones but without the usual earthen mound. So the druid circle at Cloughton may have simply been a lazy tumulus, far removed from the description of Knox’s pagan horde baying for gore on Cloughton Moor.

Knox explained that the original name for the stone circle at Cloughton was simply 'standing-stones'. He suggested that a perforated stone within the circle was a sacrificial pillar; “dedicated to Terminus, the ancient god of boundaries, who has in some manner protected this old place”. He explains that the location of the circle is named in the Whitby Abbey register as 'Swinestischarge'; a pigsty, “possibly used by the early monks of the abbey out of the hatred of the thing... too wreak their vengeance on this very ancient heathen fane by keeping their swine in this place". There are a number of stone circles in Britain that are of the same name, a name perhaps invoking Christ's Sermon on the Mount; "neither cast ye pearls before swine", do not give what is holy to those who will never accept you. However, this place was then adopted as one of the areas most important boundary marker, " … Cursed is he that removeth the landmarks! Cries Knox.- (Deut. XVii 17!!). The ancient boundary of The Liberty of Whitby Strand& Pickering Lythe passes through the circle and a line of a processional avenue of stones described by Knox may have been the line of Whitby Strand boundary stones that are still visible by the side of the fields today.

The Whitby Abbey register states that a cross-shape was added to one of the stones in the 17th century to mark it as part of the parish boundary, perhaps illustrating that the circle has always been a meeting place. This cross stone is still in situ.

Dav White Art