Wolf Land

The night of the 29th of November is St Andrew’s Eve. Since before medieval times the spirit of St Andrew has been invoked for protection on this night, using a particular prayer to specifically ward off wolves. For wolves are thought to behave very differently on this night and it is believed that they inherit special privileges on St Andrew's Eve which enables them to talk and converse with humans.

In 1798, the antiquarian Thomas Hinderwell, in his book The History and Antiquities of Scarborough and the Vicinity1 wrote; "Flixton, at the foot of the Wolds, was founded in the reign of Athelstan (924AD); there was built a hospital for the preservation of people travelling that way, that they might not be devoured by wolves. There is a certain parcel of land in this vicinity distinguished by the name 'Wolf-land' and on this spot where the Hospital anciently stood, is now a Farm house called 'Spital'”. According to ancient custom the vicar should say a solemn mass in the Spital chapel on St Andrew’s Eve. Although the chapel is no longer there, Spital Farm lies on the road to York out of Scarborough, near to the Staxton roundabout on the A64.

Wolves have worried this area for a long time according to Hinderwell, and one wolf in particular seems to have troubled the district since 1968. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, by John Harries,2 describes The Flixton Werewolf as "a fearsome beast equipped with abnormally large eyes…exuding a terrible stench…felling nocturnal wayfarers with its tail which is almost as long as its body. Its eyes are crimson and dart fire, and it roams the area of Flixton”.

In his letter to the Scarborough Review, Mr Roy Field of Hunmanby sent his valued opinion on an article I had written for the Newspaper on 'The Flixton Werewolf': “I wonder, did I inadvertently invent the werewolf 50 years ago? I was employed as a Reference and Local Studies Librarian for Scarborough Libraries. One day a reporter from the Scarborough Mercury came into the library asking for information on Folkton church, where strange lights had been seen at night. The reporter wanted to know if there were any ghost stories or legends connected to the Flixton Carr lands. I checked all the available books, but much to his disappointment came up with nothing. Was there anything else of interest, he asked? I told him about Star Carr and the discovery of various animal bones, including those of wolves. Hearing this, he perked up, made some notes, thanked me and left. I thought no more about it but was then mightily surprised, and amused, to read an article a couple of weeks later about werewolves on the Flixton Carrs! It was much later, when I was in a bookshop in Scarborough, and noted a new book on ghosts. It could well have been the 1968 book mentioned in your article. I idly glanced through it and was amazed to see that there was now an entry for Flixton and Folkton with werewolf tales. Of course what I don’t know is who the reporter talked to after me. Maybe he met someone who genuinely knew of Flixton legends that were not in my library sources. I’ll never know, but maybe ‘the truth is out there’ on those damp mysterious Carr lands”.3

Sporadic big cat sightings have been reported from the Carrs, moorland and coastline edges. A resident of Flixton informed me of his own sighting: “we saw what we thought was a dog in the field above. It was a big dog-like thing, but it didn't look like a dog, it looked like a cat, a 'dog-cat' we thought. I asked my dad about this and he said that when keeping weird exotic pets became illegal, many people chucked them out, into the wild. We thought this is what it could be, I was really scared”. John Harries Ghost Hunters Road Book also mentions a wizard: “Their (the werewolves) nocturnal exploits were supposed to be organized by a wizard whose innocent appearance enabled him to gather information about cattle, sheep and human wayfarers in taverns and market places.” 4

In Crossing the Borderlines: Guising, Masks and Ritual Animal Disguises in the European Tradition,5 Nigel Pennick explains: “At the start of each month, certain Norsemen underwent a form of madness that made them into wollves and dogs, who then spent the night roving around. Perhaps legends of werewolves originate from such ceremonial madness?” There is certainly evidence of Norsemen living in this vicinity.

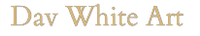

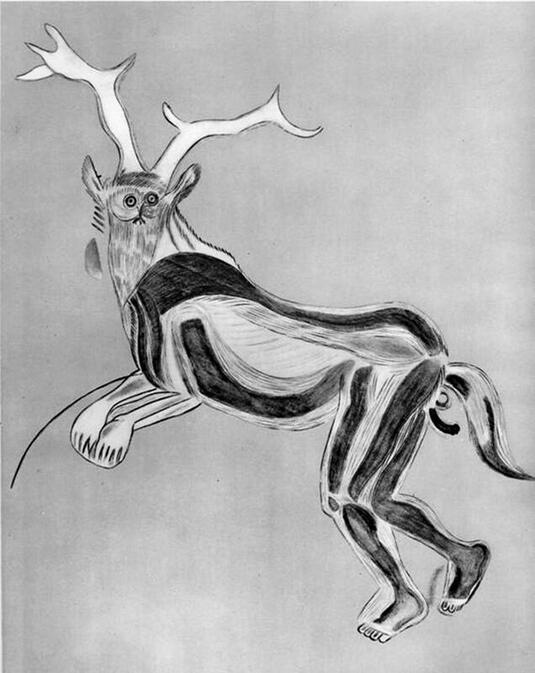

In this same parcel of ‘wolf-land’, is the famous Mesolithic settlement of Star Carr, the archaeological site that has produced many curious objects, made by the first settlers in this area 11,000 years ago. Eminent Cambridge archaeologist Sir Graham Clark, who led the initial investigations in 1949,6 saw similarities in the head-dresses recovered from the site and the shaman head-dress documented in the 17th-century by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen. Witsen recorded his observations of the remote tribes of Siberia, and his records included an illustration of a Siberian shaman or ‘devil priest’ chanting and banging a ritual drum, transforming himself wearing an antlered head-dress, reminiscent of the ones excavated at Star Carr.

Witsen’s documents were popular among the archeological community as was the consensus of the theory that shamanism was the universal religious trope that linked the dispersed tribal cultures of prehistory. The similarity of the headdress on Wisten’s drawing and the objects excavated from the peat bogs at Star Carr seemed to support this theory.

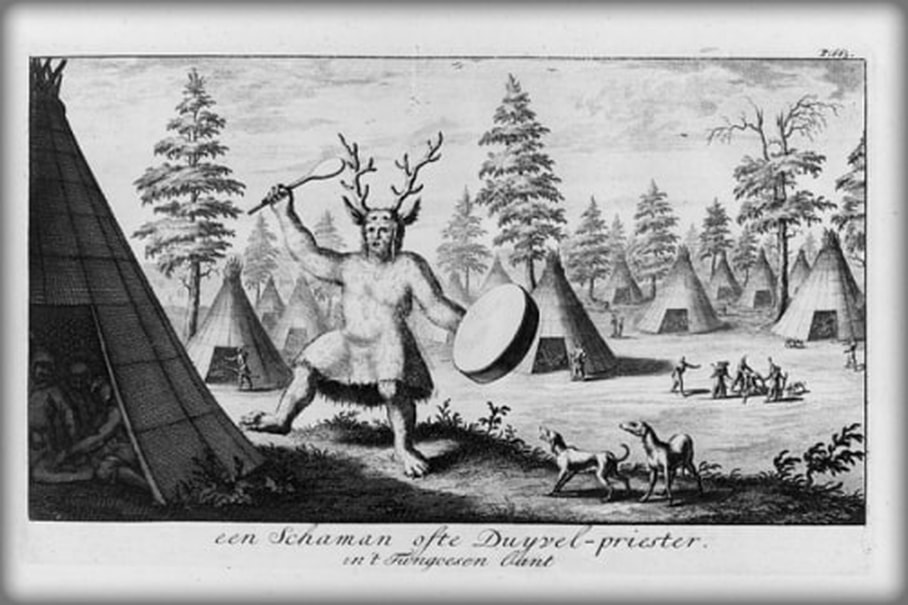

A similar thought seems to have occurred in France twenty years prior to the initial excavations at Star Carr, when the French archeologist Abbe Breuil interpreted the drawing of a peculiar figure discovered in the Cave of the Trois-Freres. Breuil was the authority on cave art and he interpreted this peculiar figure as a human transforming himself into amalgamation of different animals. The figure originally known as ‘the God of the Cave’ became known at ‘The Sorcerer’. The image, or to be precise, Breuil’s interpretation of the image is remarkably similar to Witsen’s illustration of a shaman with its wolf like feet or paws, complete with a ritual antlered headdress.

In James Frazer’s, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion he stated that tribal rituals and mythology could be classified in two principles; The Law of Similarity and The Law of Contact or Contagion. “firstly that like produces like, an effect resembles its cause; and, secondly, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other”.7 I feel the same principles apply here, and not only to the head dresses themselves and why they were made, but also to Breuil’s and Clark’s interpretations.

The modern interpretations of these objects, by Clark and Breuil, both illustrate their subject’s similarity with Witsen’s Shaman Devil Priest, who is using a deer headdress to become more wolf like. Drawing similarities with other archeological evidence to interpret their own findings is standard archeological practice. A successful archeologist interprets their own finding by drawing parallels with similar archeology, Frazier’s Law of Similarity coming into play, the archeologist is effecting the outcome of their archeology by establishing similarity.

So we have the Mesolithic makers of ritual head dresses at Star Carr and the makers of the drawing at the Cave of the Trois-Freres, creating like for like images and objects as a gesture to affect nature. And we have two academics, Clark and Breuil, pointing out the similarities to a previous document (Witsen’s). All fall under Frazier’s categorisation Principle of The The Law of Similarity. Does peat store the memory of a place? Do the rituals at Star Carr still affect this vicinity?

"Bog lands are the liveliest elements in the European landscape, not just from the point of view of flora and fauna, birds and animals, but as storing places of life, mystery and chemical change, preservers of ancient history." - Joseph Beuys,

Save our wetlands.

Dav White

Notes

1. Available on Google Books https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=04cOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA9&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

2. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, John Harris, Fredk. Muller 1968, Pg26.

3. Scarborough Review, Dec. 2016

4. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, John Harris, Fredk. Muller 1968, Pg26.

5. Crossing the Boarderlines, Nigel Pennick, Capall Bann, 1998. Pg33.

6. J.G.D. Clark, Excavations at Star Carr (1954), repub. Cambridge Uni. Press 2009.

7. The Golden Bough, Sir James George Frazer, MacmIllan 1922 Pg14.

8. Joseph Beuys, Caroline Tisdall, Thames and Hudson Ltd for The Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, 1979. Pg 39.

In 1798, the antiquarian Thomas Hinderwell, in his book The History and Antiquities of Scarborough and the Vicinity1 wrote; "Flixton, at the foot of the Wolds, was founded in the reign of Athelstan (924AD); there was built a hospital for the preservation of people travelling that way, that they might not be devoured by wolves. There is a certain parcel of land in this vicinity distinguished by the name 'Wolf-land' and on this spot where the Hospital anciently stood, is now a Farm house called 'Spital'”. According to ancient custom the vicar should say a solemn mass in the Spital chapel on St Andrew’s Eve. Although the chapel is no longer there, Spital Farm lies on the road to York out of Scarborough, near to the Staxton roundabout on the A64.

Wolves have worried this area for a long time according to Hinderwell, and one wolf in particular seems to have troubled the district since 1968. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, by John Harries,2 describes The Flixton Werewolf as "a fearsome beast equipped with abnormally large eyes…exuding a terrible stench…felling nocturnal wayfarers with its tail which is almost as long as its body. Its eyes are crimson and dart fire, and it roams the area of Flixton”.

In his letter to the Scarborough Review, Mr Roy Field of Hunmanby sent his valued opinion on an article I had written for the Newspaper on 'The Flixton Werewolf': “I wonder, did I inadvertently invent the werewolf 50 years ago? I was employed as a Reference and Local Studies Librarian for Scarborough Libraries. One day a reporter from the Scarborough Mercury came into the library asking for information on Folkton church, where strange lights had been seen at night. The reporter wanted to know if there were any ghost stories or legends connected to the Flixton Carr lands. I checked all the available books, but much to his disappointment came up with nothing. Was there anything else of interest, he asked? I told him about Star Carr and the discovery of various animal bones, including those of wolves. Hearing this, he perked up, made some notes, thanked me and left. I thought no more about it but was then mightily surprised, and amused, to read an article a couple of weeks later about werewolves on the Flixton Carrs! It was much later, when I was in a bookshop in Scarborough, and noted a new book on ghosts. It could well have been the 1968 book mentioned in your article. I idly glanced through it and was amazed to see that there was now an entry for Flixton and Folkton with werewolf tales. Of course what I don’t know is who the reporter talked to after me. Maybe he met someone who genuinely knew of Flixton legends that were not in my library sources. I’ll never know, but maybe ‘the truth is out there’ on those damp mysterious Carr lands”.3

Sporadic big cat sightings have been reported from the Carrs, moorland and coastline edges. A resident of Flixton informed me of his own sighting: “we saw what we thought was a dog in the field above. It was a big dog-like thing, but it didn't look like a dog, it looked like a cat, a 'dog-cat' we thought. I asked my dad about this and he said that when keeping weird exotic pets became illegal, many people chucked them out, into the wild. We thought this is what it could be, I was really scared”. John Harries Ghost Hunters Road Book also mentions a wizard: “Their (the werewolves) nocturnal exploits were supposed to be organized by a wizard whose innocent appearance enabled him to gather information about cattle, sheep and human wayfarers in taverns and market places.” 4

In Crossing the Borderlines: Guising, Masks and Ritual Animal Disguises in the European Tradition,5 Nigel Pennick explains: “At the start of each month, certain Norsemen underwent a form of madness that made them into wollves and dogs, who then spent the night roving around. Perhaps legends of werewolves originate from such ceremonial madness?” There is certainly evidence of Norsemen living in this vicinity.

In this same parcel of ‘wolf-land’, is the famous Mesolithic settlement of Star Carr, the archaeological site that has produced many curious objects, made by the first settlers in this area 11,000 years ago. Eminent Cambridge archaeologist Sir Graham Clark, who led the initial investigations in 1949,6 saw similarities in the head-dresses recovered from the site and the shaman head-dress documented in the 17th-century by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen. Witsen recorded his observations of the remote tribes of Siberia, and his records included an illustration of a Siberian shaman or ‘devil priest’ chanting and banging a ritual drum, transforming himself wearing an antlered head-dress, reminiscent of the ones excavated at Star Carr.

Witsen’s documents were popular among the archeological community as was the consensus of the theory that shamanism was the universal religious trope that linked the dispersed tribal cultures of prehistory. The similarity of the headdress on Wisten’s drawing and the objects excavated from the peat bogs at Star Carr seemed to support this theory.

A similar thought seems to have occurred in France twenty years prior to the initial excavations at Star Carr, when the French archeologist Abbe Breuil interpreted the drawing of a peculiar figure discovered in the Cave of the Trois-Freres. Breuil was the authority on cave art and he interpreted this peculiar figure as a human transforming himself into amalgamation of different animals. The figure originally known as ‘the God of the Cave’ became known at ‘The Sorcerer’. The image, or to be precise, Breuil’s interpretation of the image is remarkably similar to Witsen’s illustration of a shaman with its wolf like feet or paws, complete with a ritual antlered headdress.

In James Frazer’s, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion he stated that tribal rituals and mythology could be classified in two principles; The Law of Similarity and The Law of Contact or Contagion. “firstly that like produces like, an effect resembles its cause; and, secondly, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other”.7 I feel the same principles apply here, and not only to the head dresses themselves and why they were made, but also to Breuil’s and Clark’s interpretations.

The modern interpretations of these objects, by Clark and Breuil, both illustrate their subject’s similarity with Witsen’s Shaman Devil Priest, who is using a deer headdress to become more wolf like. Drawing similarities with other archeological evidence to interpret their own findings is standard archeological practice. A successful archeologist interprets their own finding by drawing parallels with similar archeology, Frazier’s Law of Similarity coming into play, the archeologist is effecting the outcome of their archeology by establishing similarity.

So we have the Mesolithic makers of ritual head dresses at Star Carr and the makers of the drawing at the Cave of the Trois-Freres, creating like for like images and objects as a gesture to affect nature. And we have two academics, Clark and Breuil, pointing out the similarities to a previous document (Witsen’s). All fall under Frazier’s categorisation Principle of The The Law of Similarity. Does peat store the memory of a place? Do the rituals at Star Carr still affect this vicinity?

"Bog lands are the liveliest elements in the European landscape, not just from the point of view of flora and fauna, birds and animals, but as storing places of life, mystery and chemical change, preservers of ancient history." - Joseph Beuys,

Save our wetlands.

Dav White

Notes

1. Available on Google Books https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=04cOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA9&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

2. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, John Harris, Fredk. Muller 1968, Pg26.

3. Scarborough Review, Dec. 2016

4. A Ghost Hunter's Road Book, John Harris, Fredk. Muller 1968, Pg26.

5. Crossing the Boarderlines, Nigel Pennick, Capall Bann, 1998. Pg33.

6. J.G.D. Clark, Excavations at Star Carr (1954), repub. Cambridge Uni. Press 2009.

7. The Golden Bough, Sir James George Frazer, MacmIllan 1922 Pg14.

8. Joseph Beuys, Caroline Tisdall, Thames and Hudson Ltd for The Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, 1979. Pg 39.