Ozymandias and The Wheatcroft Barrow

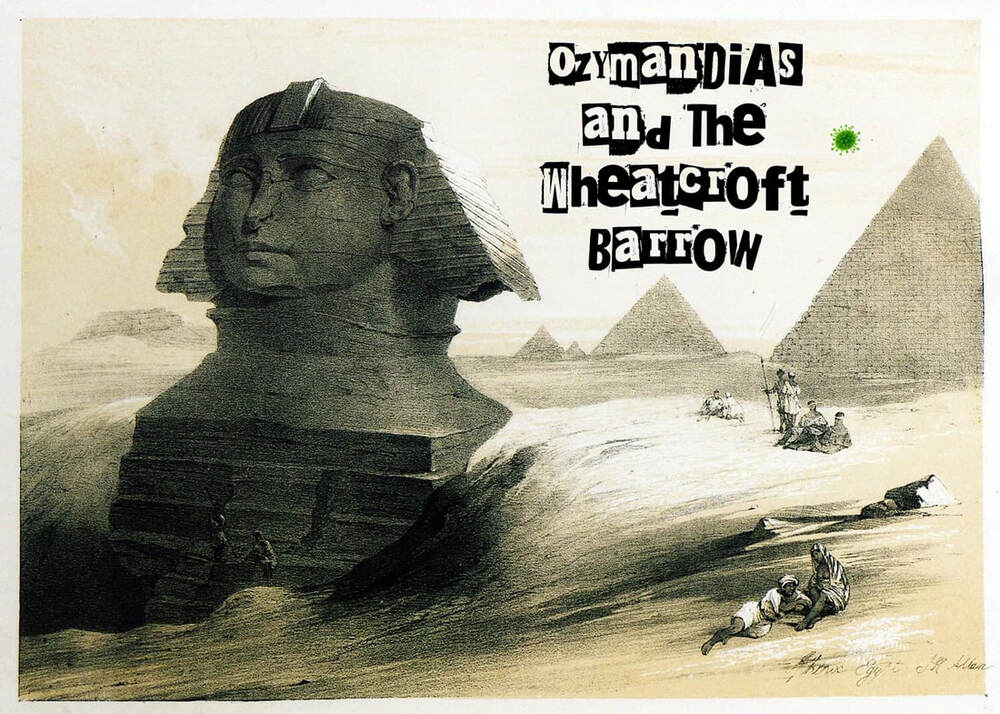

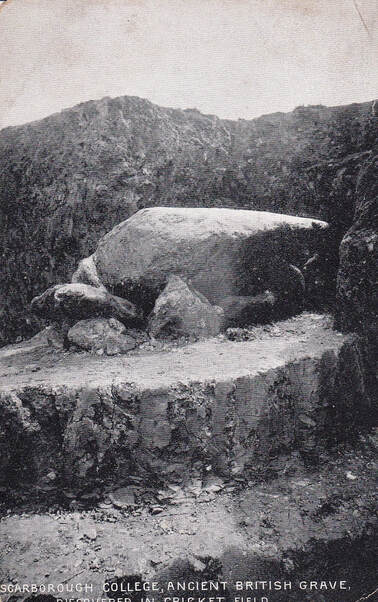

In 1910, the extension to a cricket pitch and pavilion in the grounds of Scarborough College led to the removal of the last fragments of an ancient Bronze Age burial mound known as the Wheatcroft Barrow.

Previous explorations of the barrow revealed three ‘cist’ or stone chests that held vessels containing human remains, a stone battle axe hammer and a flint knife. The stone chests where unusually ornamented with cup and ring carvings, signs to the archeologists that the individual interned was that of a great chieftain buried there up on the high cliff.

The 1930’s archeologist and curator Frank Elgee described the Wheatcroft Barrow and its contents from the museum documents; “these objects were either the treasured weapons or insignia of chiefs, a circumstance which accounts for their rarity shows that the larger barrows must be regarded as burial places of chiefs and their families.”

At the time of the realisation that the swollen prominent hillock nestled high up on the plateau at Wheatcroft was an ancient burial mound, the great archeologists of the age were traversing the British Empire on their adventures, plundering the great antiquities of the ancient world. Percy Shelly had written his great sonnet to a long dead king; ’Ozymandias’, archeologists had been tasked by the Queen to reveal the story of the nation; paying great attention Britain’s illustrious past. What an insight into the mindset of the Victorian educated classes!

Ozymandias by Percy Shelly 1818

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Percy Shelley’s sonnet describes a great King from antiquity, a commander of a great civilisation, a great civilisation which has left little trace on the landscape. A monument of a once proud ruler, and empire laid waste by time and nature. The moral being that Ozymandias goes the way of all rulers who lay claim to be god-like; they yield to entropy; nature’s second law of thermodynamics. Why else would such notable nineteenth century Christians such as Cannon Greenwell and Lord Ambercromby become archeologists? Why would they be interested in such rude pagan sites other than to strengthen their faith? Such Victorian religious zeal was found at the Kirkdale Cave and the at the grave of the 'Red Lady' on the Gower Peninsula by the Reverend William Buckland, who believed he had found the evidence of the global deluge during the time of Noah, which he felt to be the reason why the bones of hyaenas, hippopotamus and elephants had been unearthed in Britain; and with their educated dusty zealot fingers and picks they testify first hand that all else but faith is folly and will turn to dust.

And so the fate of Ozymandias mirrors the fate of this ancient chieftain interned in the barrow at Wheatcroft, and also all other chieftains who lie in the great barrows of Britain; “nothing beside remains, Round the decay of that colossal wreck.” The Wheatcroft Barrow leaves no trace on the turf that is now a cricket pavilion; “Look on my Works, ye Mighty and despair!” Tonk!

A lithograph of the Wheatcroft Barrow was made prior to its original opening in 1835. James Basire was the artist responsible for the lithograph. He was an Engraver to the Society of Antiquaries and from a family of engravers whose father of the same name is noted for apprenticing the young William Blake. The lithograph and the items found within the Wheatcroft Barrow are displayed in the Rotunda Museum. The whereabouts of the carved stone lids of the three cists found inside the Wheatcroft Barrow are currently unknown.

The Wheatcroft Barrow, as Basire’s lithograph illustrates, must have been a prominent feature on the Scarborough skyline, a man made structure well over three thousand years old, set high up on the slopes of Oliver’s Mount. It is likely that the barrow was unrecognised for what it was. Unlike other large barrows in the area, such as Willy Howe and Duggleby Howe, there are no records or local folklore mentioning the Wheatcroft Barrow outside of academic circles. There are no stories of fairies, treasure, or community gatherings, no fires burned on top, no legends of hidden gold, no rumours of the bodies of plague victims, or secret armies lying underneath. Nothing. Not even the historian Hinderwell mentions it directly, and he really liked that kind of thing.

The southern part of the landscape of Scarborough is fascinating. There are a further three other burial mounds just over the brow of Oliver’s Mount and there were actually three more burial mounds located in the grounds of Scarborough College. Wheatcroft and Weaponess was clearly an area that once meant a great deal to the ancients.

The barrows at Wheatcroft appear to be intentionally located by the stream that rises at a spring on the side of Oliver’s Mount that ran along Deepdale Avenue. The stream became known as Holbeck; Old Norse for deep hollow with beck or stream. Many of the other Barrows I mention are also located near streams around Scarborough; which begs the question of why none have been identified around the damyot beck, that most important water supply to the Scarborough old town.

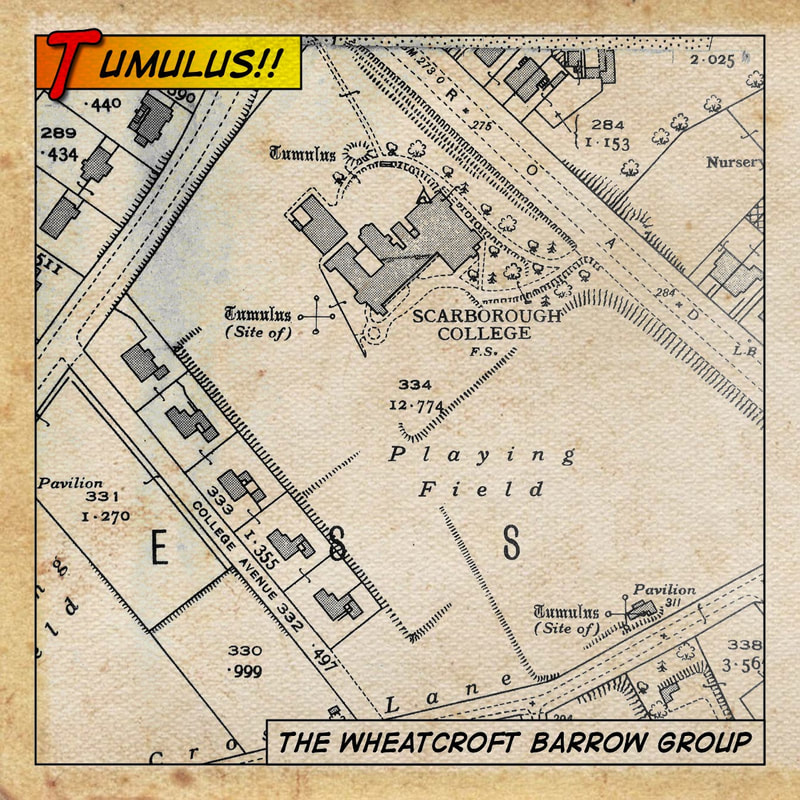

The antiquarian and former marine surveyor to the East India Company, Robert Knox made a record of his observations of this area in his 1821 map entitled, ‘A map of the county round Scarborough, in the North & East Ridings of Yorkshire : from actual trigonometrical survey with topographical geological and antiquarian descriptions.’ He documented many mounds around Scarborough which he felt were notable and interest to the antiquarians. Many tumuli no longer appear on the modern maps and have left no physical trace on the landscape of today’s Scarborough, indeed in the vicinity of Weaponess and Wheatcroft, the tumulus that once lay swollen near the bridleway from Deepdale to Eastfield Farm, is the only barrow scheduled for protection as a site of historic interest, though it has long been ploughed flat.

Knox illustrates four tumulus in the Wheatcroft area. He also illustrates two of the three High Peasholm tumulus located on the north side, either side of Peasholm Glen. Curiously he links both groups with a tumulus on Valley Road, close to Mill Beck and another on Burniston Road near to the bridge over Scalby Mills Beck. These mounds trace a bisecting line with the castle headland and suggest a clear line of sight from Wheatcroft to the High Peasholm Tumuli across an undeveloped town.

Ancient monuments lining up in a straight line is phenomena coined in 1920 by the antiquarian Alfred Watkins who called them ‘Leys’; the surveying of old straight tracks set up by the ancient Britons.

We have no clear idea about the belief system of the Bronze Age Britons, Lord Abercromby and other 19th century archaeologists held the opinion that before the invasion of British speaking people to this country, the Bronze Age culture who interred their dead in vessels such as the ones excavated at Wheatcroft, where a Gaelic speaking people. Elgee elaborated that this native Gaelic culture had close trade links to Ireland and thus shared the same place names and flare for similar decorative pattern. ‘Cala’ is the Gaelic word for harbour. Could Cala be Scarborough’s name in the Bronze Age?

“Amidst such a storm of theories, the risk of shipwreck is very great to anyone who attempts to steer a straight course.” - Frank Elgee

South of Wheatcroft is Knox Hill; Gaelic for hill, ‘cnoc’. The hill leads to a bridleway that leads across the Carrs via Cayton and Folkton to Spella Howe. Spella Howe or Speech Mound, once another impressive tumulus, located on what was once known as Knock Hill, Knock also a derivative of ‘cnoc’ and a meeting place of the Torbar Hundred, a local land division mentioned in the Doomsday Book. On Scarborough’s North side at the other end of this ley that we have imagined are the High Peasholm tumuli, the area where the Crown Steward and Bailiff of Northstead can “Take the Chiltern Hundreds", referring to the legal fiction used to resign from the House of Commons. Torbar One Hundred to the South, Chiltern One Hundred to the North connected by a straight line of tumuli, one of which was of a great chieftain. Its fascinating how one can draw a line in the vicinity and uncover so much that is interesting.

DavWhiteArt.com

In 1910, the extension to a cricket pitch and pavilion in the grounds of Scarborough College led to the removal of the last fragments of an ancient Bronze Age burial mound known as the Wheatcroft Barrow.

Previous explorations of the barrow revealed three ‘cist’ or stone chests that held vessels containing human remains, a stone battle axe hammer and a flint knife. The stone chests where unusually ornamented with cup and ring carvings, signs to the archeologists that the individual interned was that of a great chieftain buried there up on the high cliff.

The 1930’s archeologist and curator Frank Elgee described the Wheatcroft Barrow and its contents from the museum documents; “these objects were either the treasured weapons or insignia of chiefs, a circumstance which accounts for their rarity shows that the larger barrows must be regarded as burial places of chiefs and their families.”

At the time of the realisation that the swollen prominent hillock nestled high up on the plateau at Wheatcroft was an ancient burial mound, the great archeologists of the age were traversing the British Empire on their adventures, plundering the great antiquities of the ancient world. Percy Shelly had written his great sonnet to a long dead king; ’Ozymandias’, archeologists had been tasked by the Queen to reveal the story of the nation; paying great attention Britain’s illustrious past. What an insight into the mindset of the Victorian educated classes!

Ozymandias by Percy Shelly 1818

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Percy Shelley’s sonnet describes a great King from antiquity, a commander of a great civilisation, a great civilisation which has left little trace on the landscape. A monument of a once proud ruler, and empire laid waste by time and nature. The moral being that Ozymandias goes the way of all rulers who lay claim to be god-like; they yield to entropy; nature’s second law of thermodynamics. Why else would such notable nineteenth century Christians such as Cannon Greenwell and Lord Ambercromby become archeologists? Why would they be interested in such rude pagan sites other than to strengthen their faith? Such Victorian religious zeal was found at the Kirkdale Cave and the at the grave of the 'Red Lady' on the Gower Peninsula by the Reverend William Buckland, who believed he had found the evidence of the global deluge during the time of Noah, which he felt to be the reason why the bones of hyaenas, hippopotamus and elephants had been unearthed in Britain; and with their educated dusty zealot fingers and picks they testify first hand that all else but faith is folly and will turn to dust.

And so the fate of Ozymandias mirrors the fate of this ancient chieftain interned in the barrow at Wheatcroft, and also all other chieftains who lie in the great barrows of Britain; “nothing beside remains, Round the decay of that colossal wreck.” The Wheatcroft Barrow leaves no trace on the turf that is now a cricket pavilion; “Look on my Works, ye Mighty and despair!” Tonk!

A lithograph of the Wheatcroft Barrow was made prior to its original opening in 1835. James Basire was the artist responsible for the lithograph. He was an Engraver to the Society of Antiquaries and from a family of engravers whose father of the same name is noted for apprenticing the young William Blake. The lithograph and the items found within the Wheatcroft Barrow are displayed in the Rotunda Museum. The whereabouts of the carved stone lids of the three cists found inside the Wheatcroft Barrow are currently unknown.

The Wheatcroft Barrow, as Basire’s lithograph illustrates, must have been a prominent feature on the Scarborough skyline, a man made structure well over three thousand years old, set high up on the slopes of Oliver’s Mount. It is likely that the barrow was unrecognised for what it was. Unlike other large barrows in the area, such as Willy Howe and Duggleby Howe, there are no records or local folklore mentioning the Wheatcroft Barrow outside of academic circles. There are no stories of fairies, treasure, or community gatherings, no fires burned on top, no legends of hidden gold, no rumours of the bodies of plague victims, or secret armies lying underneath. Nothing. Not even the historian Hinderwell mentions it directly, and he really liked that kind of thing.

The southern part of the landscape of Scarborough is fascinating. There are a further three other burial mounds just over the brow of Oliver’s Mount and there were actually three more burial mounds located in the grounds of Scarborough College. Wheatcroft and Weaponess was clearly an area that once meant a great deal to the ancients.

The barrows at Wheatcroft appear to be intentionally located by the stream that rises at a spring on the side of Oliver’s Mount that ran along Deepdale Avenue. The stream became known as Holbeck; Old Norse for deep hollow with beck or stream. Many of the other Barrows I mention are also located near streams around Scarborough; which begs the question of why none have been identified around the damyot beck, that most important water supply to the Scarborough old town.

The antiquarian and former marine surveyor to the East India Company, Robert Knox made a record of his observations of this area in his 1821 map entitled, ‘A map of the county round Scarborough, in the North & East Ridings of Yorkshire : from actual trigonometrical survey with topographical geological and antiquarian descriptions.’ He documented many mounds around Scarborough which he felt were notable and interest to the antiquarians. Many tumuli no longer appear on the modern maps and have left no physical trace on the landscape of today’s Scarborough, indeed in the vicinity of Weaponess and Wheatcroft, the tumulus that once lay swollen near the bridleway from Deepdale to Eastfield Farm, is the only barrow scheduled for protection as a site of historic interest, though it has long been ploughed flat.

Knox illustrates four tumulus in the Wheatcroft area. He also illustrates two of the three High Peasholm tumulus located on the north side, either side of Peasholm Glen. Curiously he links both groups with a tumulus on Valley Road, close to Mill Beck and another on Burniston Road near to the bridge over Scalby Mills Beck. These mounds trace a bisecting line with the castle headland and suggest a clear line of sight from Wheatcroft to the High Peasholm Tumuli across an undeveloped town.

Ancient monuments lining up in a straight line is phenomena coined in 1920 by the antiquarian Alfred Watkins who called them ‘Leys’; the surveying of old straight tracks set up by the ancient Britons.

We have no clear idea about the belief system of the Bronze Age Britons, Lord Abercromby and other 19th century archaeologists held the opinion that before the invasion of British speaking people to this country, the Bronze Age culture who interred their dead in vessels such as the ones excavated at Wheatcroft, where a Gaelic speaking people. Elgee elaborated that this native Gaelic culture had close trade links to Ireland and thus shared the same place names and flare for similar decorative pattern. ‘Cala’ is the Gaelic word for harbour. Could Cala be Scarborough’s name in the Bronze Age?

“Amidst such a storm of theories, the risk of shipwreck is very great to anyone who attempts to steer a straight course.” - Frank Elgee

South of Wheatcroft is Knox Hill; Gaelic for hill, ‘cnoc’. The hill leads to a bridleway that leads across the Carrs via Cayton and Folkton to Spella Howe. Spella Howe or Speech Mound, once another impressive tumulus, located on what was once known as Knock Hill, Knock also a derivative of ‘cnoc’ and a meeting place of the Torbar Hundred, a local land division mentioned in the Doomsday Book. On Scarborough’s North side at the other end of this ley that we have imagined are the High Peasholm tumuli, the area where the Crown Steward and Bailiff of Northstead can “Take the Chiltern Hundreds", referring to the legal fiction used to resign from the House of Commons. Torbar One Hundred to the South, Chiltern One Hundred to the North connected by a straight line of tumuli, one of which was of a great chieftain. Its fascinating how one can draw a line in the vicinity and uncover so much that is interesting.

DavWhiteArt.com