The Colossus of St Nicholas Cliff

For over 150 years the Grand Hotel has been one of Scarborough’s most iconic buildings. It is difficult to imagine what the ordinary townsfolk thought of it when its mortar was still fresh, standing proud of a bay filled with the humble fishermen’s houses of the old town.

Opulent, bombastic and extravagant, it was built in the high Victorian baroque style, known for its theatrical ostentations.

Scarborough and District Civic Society, in its booklet The Streets of Scarborough, describes the Grand as: “Unclassifiable but unmistakably and thoroughly English”.

This titan was bigger than the colossus of Rhodes and once the largest hotel in Europe. Its exterior is garnished with over 100 over-sized scrolled modillions and plump stone festoon garlands made especially for this architectural feast. The carved figures of Hercules, draped in a lion skin, and the four fates that appear in the myth of his trials appear along the top levels of the building as caryatid, meaning a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support. The carved figures of putti also feature along the roof tops. Putti are cherubs representing inspiration and the omnipresence of God.

The Grand was constructed in a V shape to honour Queen Victoria. Her statue in the town-hall gardens, installed 30 years after the Grand was built, was placed along the central axis of the V shape that aligns with north and south and with the Grand’s great staircase inside. The staircase is based on the one in Berlin Opera House. Architect Cuthbert Brodrick, known for his attention to detail, fashioned the width of the staircase to allow two fully crinolined ladies and their escorts to pass on the stairs without upstaging each other. The space on the landing was contrived so that a lady could observe those in the hall below and on the staircase, to choose her moment to make an entrance.

Brodrick’s other notable buildings include the town hall and city museum in Leeds, known for their gigantism. The purpose of architectural gigantism is to inspire the pedestrian, to make you look up, to uplift you, to encourage you to dream of what is possible in the presence of such buildings. The statues of Hercules at the top of the Grand are looking down at you, over the cornicing.

In his booklet A Brief History of the Grand Hotel, Bryan Perrett remarked that it was celebrated “to some for its sheer naked arrogance” and “was an immense architectural extravaganza on the scale of Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria’s Neuschwanstein castle”. He was referring to the Grand’s Wagnerian theatrical pretence. Churchill stayed at the hotel a few times during Conservative party conferences. If he was, say, the Wagnerian hero Siegfried, then the Valkyrie would have to be the SAS, who trained at the Grand after the seizure of the Iranian embassy in 1980s.

Ludwig, a devoted patron of Wagner, bankrupted his country by creating theatrical fairy-tale castles based on Germanic myth. His beautiful buildings were follies and deceptions. Behind the fake medieval vaulting and fairy grottos were steel girders and the nuts and bolts of contemporary construction methods. Neuschwanstein Castle inspired the Disney Corporation when building the Sleeping Beauty castle that features in Disney parks around the world. Neuschwanstein Castle was the castle featured in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The Grand was built at a time of restructure in Scarborough. The dynamics of the town’s main approaches and thoroughfares were changing. The old approach to the town via Castle Road through the Auborough gate had become redundant. The new hotels and grand stucco terraces built on the South Cliff were aimed at attracting wealthy visitors and the Esplanade would bring them into town via the Spa bridge.

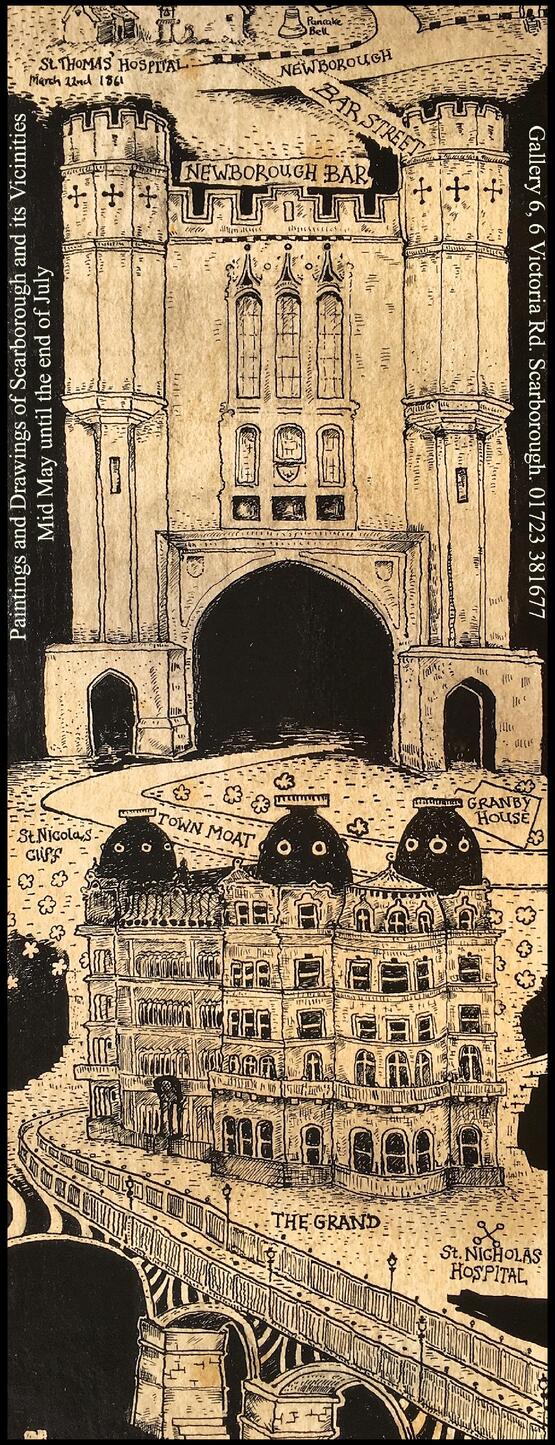

Visitors could marvel at the the Grand as they entered the town towards Newborough gate; a new fairy-tale folly replacing a 12th century bar that had stood for nearly 500 years. The new gate was a tourist attraction. Its theatrical parapets, castellations, arrow slits and gothic archways would welcome visitors to our historical town. After passing through it, they could walk up Queen Street to the new stucco terraces on Castle Road, Blenheim Terrace and New Queen Street, to stroll along the north-bay prom or up to St Mary’s Church and the castle. This would spare them the sight of the poor housing of the old-town, whose residents had not yet been relocated to Eastfield, Edge Hill and Barrowcliff. The Spa bridge was armed with a toll gate to prevent natives from crossing over to the South Cliff.

As Hunter S Thompson might have said: “They had the momentum; they were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. So now, you can go up on a steep hill, say where Birdcage Walk meets the Esplanade and look north across the south bay, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark on the high Victorian terraces — that place where the beautiful wave of commerce finally broke, and rolled back”.

The fairytale Newborough bar would soon be sacrificed to commerce when the town opted for a system of trams which wouldn’t fit under its gothic arch. To get an idea of how the bar appeared, you have only to look at the former gaol on Dean Road and the Towers building at Mulgrave Place. Both feature the same theatrical medieval features of turrets, arrow slits and castellations. The old prison also features the same type of gothic archway that a tram wouldn’t fit under. And the Grand still welcomes visitors.

Dav White Art

For over 150 years the Grand Hotel has been one of Scarborough’s most iconic buildings. It is difficult to imagine what the ordinary townsfolk thought of it when its mortar was still fresh, standing proud of a bay filled with the humble fishermen’s houses of the old town.

Opulent, bombastic and extravagant, it was built in the high Victorian baroque style, known for its theatrical ostentations.

Scarborough and District Civic Society, in its booklet The Streets of Scarborough, describes the Grand as: “Unclassifiable but unmistakably and thoroughly English”.

This titan was bigger than the colossus of Rhodes and once the largest hotel in Europe. Its exterior is garnished with over 100 over-sized scrolled modillions and plump stone festoon garlands made especially for this architectural feast. The carved figures of Hercules, draped in a lion skin, and the four fates that appear in the myth of his trials appear along the top levels of the building as caryatid, meaning a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support. The carved figures of putti also feature along the roof tops. Putti are cherubs representing inspiration and the omnipresence of God.

The Grand was constructed in a V shape to honour Queen Victoria. Her statue in the town-hall gardens, installed 30 years after the Grand was built, was placed along the central axis of the V shape that aligns with north and south and with the Grand’s great staircase inside. The staircase is based on the one in Berlin Opera House. Architect Cuthbert Brodrick, known for his attention to detail, fashioned the width of the staircase to allow two fully crinolined ladies and their escorts to pass on the stairs without upstaging each other. The space on the landing was contrived so that a lady could observe those in the hall below and on the staircase, to choose her moment to make an entrance.

Brodrick’s other notable buildings include the town hall and city museum in Leeds, known for their gigantism. The purpose of architectural gigantism is to inspire the pedestrian, to make you look up, to uplift you, to encourage you to dream of what is possible in the presence of such buildings. The statues of Hercules at the top of the Grand are looking down at you, over the cornicing.

In his booklet A Brief History of the Grand Hotel, Bryan Perrett remarked that it was celebrated “to some for its sheer naked arrogance” and “was an immense architectural extravaganza on the scale of Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria’s Neuschwanstein castle”. He was referring to the Grand’s Wagnerian theatrical pretence. Churchill stayed at the hotel a few times during Conservative party conferences. If he was, say, the Wagnerian hero Siegfried, then the Valkyrie would have to be the SAS, who trained at the Grand after the seizure of the Iranian embassy in 1980s.

Ludwig, a devoted patron of Wagner, bankrupted his country by creating theatrical fairy-tale castles based on Germanic myth. His beautiful buildings were follies and deceptions. Behind the fake medieval vaulting and fairy grottos were steel girders and the nuts and bolts of contemporary construction methods. Neuschwanstein Castle inspired the Disney Corporation when building the Sleeping Beauty castle that features in Disney parks around the world. Neuschwanstein Castle was the castle featured in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The Grand was built at a time of restructure in Scarborough. The dynamics of the town’s main approaches and thoroughfares were changing. The old approach to the town via Castle Road through the Auborough gate had become redundant. The new hotels and grand stucco terraces built on the South Cliff were aimed at attracting wealthy visitors and the Esplanade would bring them into town via the Spa bridge.

Visitors could marvel at the the Grand as they entered the town towards Newborough gate; a new fairy-tale folly replacing a 12th century bar that had stood for nearly 500 years. The new gate was a tourist attraction. Its theatrical parapets, castellations, arrow slits and gothic archways would welcome visitors to our historical town. After passing through it, they could walk up Queen Street to the new stucco terraces on Castle Road, Blenheim Terrace and New Queen Street, to stroll along the north-bay prom or up to St Mary’s Church and the castle. This would spare them the sight of the poor housing of the old-town, whose residents had not yet been relocated to Eastfield, Edge Hill and Barrowcliff. The Spa bridge was armed with a toll gate to prevent natives from crossing over to the South Cliff.

As Hunter S Thompson might have said: “They had the momentum; they were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. So now, you can go up on a steep hill, say where Birdcage Walk meets the Esplanade and look north across the south bay, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark on the high Victorian terraces — that place where the beautiful wave of commerce finally broke, and rolled back”.

The fairytale Newborough bar would soon be sacrificed to commerce when the town opted for a system of trams which wouldn’t fit under its gothic arch. To get an idea of how the bar appeared, you have only to look at the former gaol on Dean Road and the Towers building at Mulgrave Place. Both feature the same theatrical medieval features of turrets, arrow slits and castellations. The old prison also features the same type of gothic archway that a tram wouldn’t fit under. And the Grand still welcomes visitors.

Dav White Art